This blog is cross-posted from the World Economic Forum Global Technology Governance Summit blog, under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License. It was written by Claudia Vickers, Megan Palmer, Jennifer Molloy and Elissa Prichep.

- Synthetic biology brings together multiple disciplines to design useful things from the building blocks of life.

- Realizing the future potential of synthetic biology to benefit people and the planet requires revisiting what types of societal transformations we desire.

- Synthetic Biology Global Future Council discussions identify that revisiting our visions for the future should begin by centring values: equity, sustainability, solidarity and humility.

This week the World Economic Forum is hosting the Global Technology Governance Summit, which aims to be the foremost global multi-stakeholder gathering dedicated to the responsible design and deployment of emerging technologies through public-private collaboration. At the top of the agenda is synthetic biology, reflecting a moment when the world’s attention is focused not only on the vital role biological technologies play in protecting against biological threats, but also on the potential of these technologies to help transform our societies during the Great Reset.

Realizing the future potential of synthetic biology to benefit people and the planet requires revisiting what types of societal transformations we desire and why past approaches have missed the mark. For example, inequitable access to technology enabled by synthetic biology is hitting the headlines as we contend with global disparities in the development, manufacture and distribution of COVID-19 vaccines. The new Global Future Council on Synthetic Biology is examining how to centre values of equity, humility, solidarity and sustainability so that as we learn to engineer the living world, we are ensuring it is a world in which we want to live.

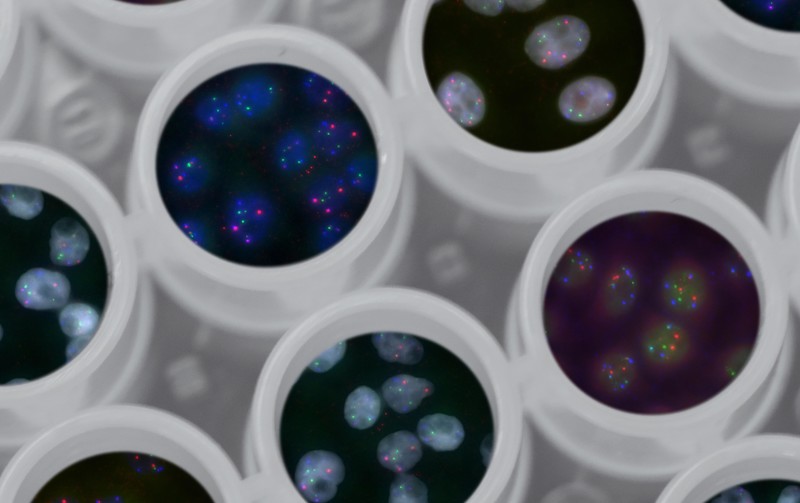

Synthetic biology brings together multiple disciplines – across the biological sciences, computer science, engineering, social sciences and beyond – to design useful things from the building blocks of life. Tools to synthesise and engineer biological systems, enabled by growing repositories of DNA-encoded biological components, offer new approaches for a startlingly wide range of applications across health, manufacturing, energy and beyond. This ability promises to revolutionise economies and societies, offering new approaches to transform (and perhaps even ‘biologise’) industries and overcome global challenges to benefit people and the planet.https://www.youtube.com/embed/tns8vpgacRk?enablejsapi=1&wmode=transparent

The world is grappling with how to transform the unsustainable practices that we rely on to support economic development and meet human needs. Biology offers inspiration and hope: it has been solving problems to enable our planet to thrive for around 3.5 billion years. But evolution takes time, and it’s not necessarily targeted towards the outcomes that we desire. In a rapidly changing world that is facing major global challenges, from climate change to pandemics, synthetic biology can provide the tools to engineer biological processes that can deliver targeted, rapid and sustainable solutions. But to succeed we must go beyond asking ‘What can we do?’, to ask: ‘What should we do?’, ‘How should we do it?’, ‘Who should do it?’ and, of course, “Who will do it?”.

What can synthetic biology achieve?

If you’ve had an Impossible Burger, you’ve already had a synthetic biology experience. Impossible Foods produce a plant protein called leghaemaglobin to provide flavour and other properties to their plant-based meat replacement products. It’s made by taking the plant gene and putting it into a microbe, then brewing up the gene-encoded protein in almost the same way that beer is made. The protein is extracted from the brew and blended with other plant-based components to deliver the burger patty. Beyond sparing animal lives, these alternatives can help transform industries with massive carbon footprints.

Synthetic biology can also enable the engineering of improved crops that deliver more food from less farmland and decrease emissions by reducing reliance on synthetic fertilisers. Animal and human health applications are also vast, and include improved and novel diagnostics, new production platforms for drugs and vaccines, and precisely tailored therapeutics that even leverage your own cells to fight cancer. Perhaps the most topical of these right now are the mRNA coronavirus vaccines – a novel vaccine technology developed, tested and delivered within 12 months of the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Manufacturing can also be transformed through industrial bio-based ‘green’ chemicals, biodegradable plastics and fibres that replace unsustainable petrochemical-based products.

There are many more applications, from monitoring and remediating environmental contamination, managing invasive pests and pathogens, reviving endangered species, and engineering resilience against climate change, to enabling new strategies to store data. The ability to learn from and leverage technology that has already made the living world offers seemingly endless opportunities.

Yet these are still early days. Synthetic biology is a relatively new field, discipline and community – it has only formally been around for a few decades, but has already demonstrated its value and is growing exponentially. Significant public and private investment has driven this growth, and the investments, markets and impacts are projected to only grow. Technological roadmaps and regional strategic plans for synthetic biology have already emerged, along with communities focused on science and technology, technology and culture, business and finance, and equipping the next generation.The field also has a long history of engagement with how we can leverage biotechnologies to improve our security, as well as manage accidents and misuse.

The opportunities are profound and many of our current challenges compel urgent action, but there is also a need for realism, tempering and focus to allow synthetic biology to deliver its full potential in a way that benefits all people and the planet. If we do not carefully consider the broader socioeconomic, environmental and global context in which this technology is being developed and deployed, and if we do not effectively identify the pathways to greatest impact, synthetic biology will fail to deliver on its potential to improve lives.

Charting a path to realize synthetic biology’s potential

To help address the challenges of how a quickly maturing field might bend its trajectory towards creating futures we desire, the World Economic Forum has recently formed the new Synthetic Biology Global Future Council. The Council aims to bring together diverse stakeholders from across the globe, across sectors and across perspectives to envision ideal future states of synthetic biology and strategies to ensure more peaceful, prosperous, sustainable and equitable societies.

Our work builds on previous efforts and focuses on inherently global challenges that concern how we synthesise our shared biological futures and contend with our own biological nature: Who gets to envision the future? Who gets to shape it? How will the future transform us? This is no small task, and while the Council is small, it brings together a cohort committed to reflection and action that enables others to contribute to this mission.

Four themes for the future

While the Council’s work has only recently begun, early discussions clearly identified that revisiting and re-envisioning our visions for the future should begin by centring values, including equity, sustainability, solidarity and humility. Moreover, by decentring technologies as either the primary problem or solution we can help expose systemic challenges and opportunities. We are critically and constructively examining the history and current state of the field with a view to developing scenarios and strategies to deliver a brighter future.

- Equity considers fairness, inclusion, distribution, justice and benefits. It considers resource flows, including who is providing, who is paying, who is profiting and who is taking risk. It includes intergenerational issues, minority stakeholders, Indigenous peoples, knowledge sources, data access and use, different physical and political geographies, and biological resources. It prioritises truly global, effectual and achievable targets for the field.

- Sustainability considers sustainable outcomes, circular bioeconomy and the capacity for humanity to coexist with the Earth’s biosphere without exhausting the Earth’s resources. Sustainability can be achieved when triple bottom-line outcomes – environmental, social and economic – intersect in such a way that resource utilisation is optimised and does not unreasonably cause harm.

- Solidarity considers the need for inclusion and support within both the science and the narrative. It includes shared objectives and interests, support, and unity across groups – even when they have different initial priorities. In our context, it brings together people from across the globe working for common aims.

- Humility recognises how much we still have to learn about engineering biology, and is critical of hype and unfulfilled promises. It demands respect for the innate complexity of biology, and considers what can and should be done in the context of what we imagine – and what we claim – might be possible to do.

While these themes are only starting points, we believe them to be critical to synthetic biology realizing its potential to generate a better future for people and the planet. The council cannot – and should not – do this alone. But we hope to start a conversation about how we can meet this moment in which the power of biology to transform our world – and ourselves – is on everyone’s minds. We welcome your ideas and input as we look to work together in new ways.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

Written by

- Claudia Vickers, Director, CSIRO, Synthetic Biology Future Science Platform

- Megan Palmer, Adjunct Professor; Executive Director, Bio Policy and Leadership Initiatives, Department of Bioengineering, Stanford University

- Jennifer Molloy, Shuttleworth Research Fellow, University of Cambridge

- Elissa Prichep, Project Lead Precision Medicine, World Economic Forum

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Image Credit: Three-dimensional landscape of genome, National Cancer Institute